Welcome to Accidental Sagacity! What, you ask, is this curious place? Stay with me, its meaning shall soon unfold.

This Substack began, as most things do, by accident. Then came the sagacity. Or maybe it was the other way around. It hardly matters.

The phrase described the coining of a new word by Horace Walpole in 1754, but I didn’t know that yet. I encountered it while reading The Pleasure of Reading in an Age of Distraction by Alan Jacobs—a book I had picked up in the hopes of justifying the tower of unread books on my desk, or perhaps finding guidance on how one ought to read. I found myself scribbling in the margins, questioning every thought before the ink had even dried.

But it did more than that. It unraveled rules I’d been too eager to collect, years of grasping for guidance without pausing to examine (hat tip to Mortimer J. Adler). It led me to poetry I never thought I’d enjoy, and to a Persian tale from the late Middle Ages.

Jacobs writes almost apologetically, that “most of our growth as readers cannot be planned.” We must “consent to be guided by the invisible hand of serendipity.” I flinched. Not because I disagreed, but because I had stopped believing in the word.

Once, serendipity meant something. But in recent years, it felt stripped of its mystery. The British named it their favorite word in 2000, surpassing ‘Quidditch,’ which took second place!1

By the pandemic, it was everywhere—serendipitous encounters, engineered luck. We were expanding our surface area for discovery, as if slapping a pretty word on the internet, could alchemize extraction into discovery.

Online, we weren’t so much wandering as we were curating selves and uploading all things pseudonymous, composite, and aspirational. We optimized for maximum stumble-upon-ability, hoping that proximity to influence, or the gravity of a crowd, might turn signal into significance. Serendipity became the currency of attention, not accident.

But Jacobs argued otherwise, at least in terms of reading: “Fortuity happens, but serendipity can be cultivated. You can grow in serendipity. You can even become a disciple of serendipity.” I wanted to believe that again. So, I went looking. I realized that, somewhere in the industrialization of luck, we had forgotten what the word actually means.

The Tale, Please

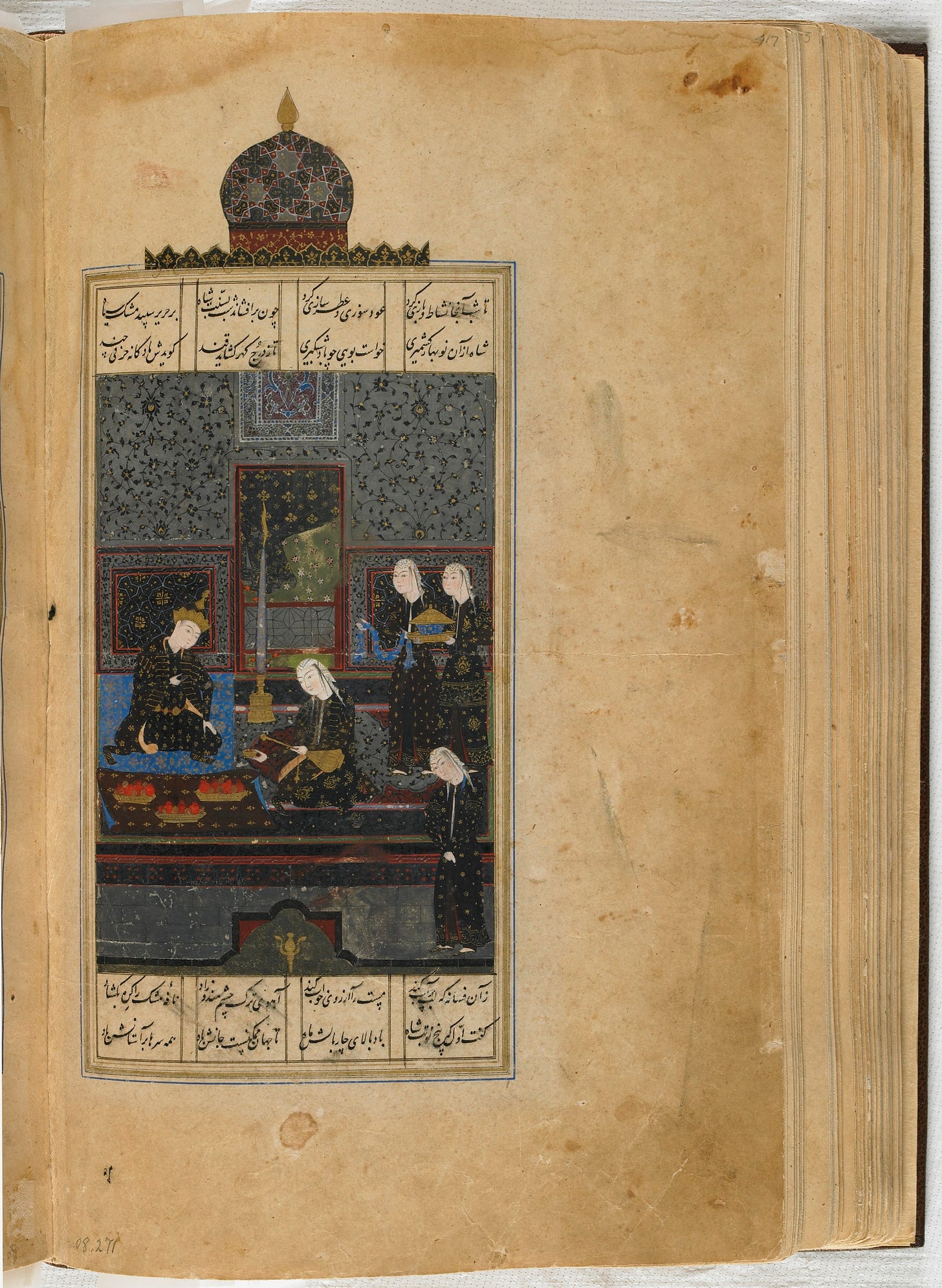

The tale begins around 1302 (with roots tracing back to the 10th century),2 in a collection of Persian masnavis3 by Amir Khusro called Hasht-Bihisht (The Eight Paradises). In one, King Bahram Gur visits seven pavilions, each home to a princess from a different land. In the black pavilion, on a Saturday, the Indian princess tells a story.

Three princes of Serendip (an ancient name for Sri Lanka) set out on a journey. In the desert, they meet a merchant whose camel has gone missing. They haven’t seen the animal, but are able to describe it exactly: blind in one eye, missing a tooth, lame in one leg, carrying honey on one side and butter on the other, and with a pregnant woman.

They are accused of theft and dragged before the emperor. Just before execution, they locate the camel. The princes are declared innocent. In fact, they are extraordinary.

The Emperor asks them to explain their wisdom, and they share their observations from the trail: chewed grass was thinner on one side (blind in one eye), only three footprints (lame leg), ants on one side (butter), flies on the other (honey), and urine near a set of handprints (pregnant woman – bit of a reach, but it is the 14th century).

The story continues with more characters, clues, and consequences. It is far from a simple fairy tale with dark undertones lurking at each turn. The original idea suggests something much more wondrous—the world constantly speaks in a language of signs, symbols, and coincidences that we're usually too distracted to translate. It's a proto-detective story. A tribute to the prepared mind.

The tale traveled many miles, languages, and centuries. From Persian to Italian (1557), then French, and eventually English. However, the English version is not a direct translation from the original but is instead based on one of the intermediaries. Despite extensive searching, I have been unable to locate a direct translation.

In 1754, Walpole coined serendipity in a letter to Sir Horace Mann, inspired by a Venetian coat of arms he was researching on what seems to have been a mundane Monday. He wrote:

This discovery I made by a talisman, which Mr. Chute calls the Sortes Walpoliance, by which I find every thing I want, a pointe nommée, whenever I dip for it. This discovery, indeed, is almost of that kind which I call Serendipity, a very expressive word, which, as I have nothing better to tell you, I shall endeavor to explain to you: you will understand it better by the derivation than the definition. I once read a silly fairy tale, called “The Three Princes of Serendip”: as their Highnesses travelled, they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of: for instance, on the them discovered that a mule blinds of the right eye had travelled the same road lately, because the grass was eaten only on the left side, where it was worse than on the right—now do you understand Serendipity? One of the most remarkable instances of this accidental sagacity, (for you must observe that no discovery of a thing you are looking for comes under this description,) was of my Lord Shaftsbury, who, happening to dine at Lord Chancellor Clarendon’s, found out the marriage of the Duke of York and Mrs. Hyde, by the respect with which her mother treated her at table.

That Walpole would refer to Amir Khusro’s layered, centuries-old parable as ‘a silly fairy tale’ feels like a kind of literary sacrilege—but I digress. The word mostly slept until 1910, when it surfaced as an adjective in a fishing guide (I know, right?):

“With good luck you should catch a three-pounder, among others, with very good luck a four-pounder. Those who Horace Walpole, I believe, called serendipitous catch a five-pounder now and again.” — H. T. Sheringham, An Open Creel 1910

From fish to feeds, somewhere along the way, we hyper-optimized the proverbial accident out of life. Algorithms now serve us more of what we already like. Fewer chances to stumble upon anything remarkable beyond our existing tastes.

I’ve picked up most of my hobbies through glorified stumbling, and I owe my rediscovery of reading and writing to it too. I used to apologize for this haphazard, largely self-taught education.

But I think Jacobs is right: “The cultivation of serendipity is an option for anyone... but for people living in conditions of prosperity and security and informational richness it is something vital.” It’s exactly the kind of life-affirming fuel any autodidact in this age could use.

I don’t know what this publication will become. Maybe a quiet haven for drift and digression. A place for the footnote that outshines the chapter. The wrong turn that, in retrospect, was the only way forward.

If you’ve made it this far, I hope this Substack might one day be a serendipitous stumble in your feed.

Ha! From the BBC article, “both words were more popular than evocative and emotional terms like love (3rd), peace (4th), hope (6th) and Jesus (10th), which might have been expected to top the poll.”

Deep roots. An epic from around 1010, Shahnameh by Firdausi, inspired another epic in 1197, Haft Paykar by Nizami, which in turn inspired the set of tales that eventually found their way onto Horace Walpole’s reading list.

A narrative style of poem in rhymed couplets.

Not to bring down the tone but one of my favourite movies growing up was the rom-com of the same name, with Kate Beckinsale and John Cusack. It introduced me to the word (and also Gabriel Garcia Marquez), but I had no idea of its origins until now!

In the movie, the characters meet each other serendipitously but are both in other relationships, so they pin their reunion on the chance of a similar moment. In the end, neither of them can stand the wait and each go out in search of the other.

It’s funny that Walpole reckoned you can’t find anything you’re actually looking for serendipitously, and Jacobs argued serendipity could be ‘cultivated’. This reminds me of the old adage that says you usually need to spend time, both with the blank page and out in the world, doing other things for inspiration to come.